The President of E Pluribus University and founder of thrivela.org, Perry Goldberg, joins host Robert Strock to discuss current efforts to identify solutions and barriers to the growing homelessness problem in California. Current solutions involve building affordable housing where land runs at a premium and laws, regulations, and objections of neighbors add to the expense and time it takes to develop the properties. The results are not enough housing for a growing vulnerable population. Both Goldberg and Strock point toward a pervasive false perception of the majority of the unsheltered being addicted, mentally ill, or unable to contribute to society.

The President of E Pluribus University and founder of thrivela.org, Perry Goldberg, joins host Robert Strock to discuss current efforts to identify solutions and barriers to the growing homelessness problem in California. Current solutions involve building affordable housing where land runs at a premium and laws, regulations, and objections of neighbors add to the expense and time it takes to develop the properties. The results are not enough housing for a growing vulnerable population. Both Goldberg and Strock point toward a pervasive false perception of the majority of the unsheltered being addicted, mentally ill, or unable to contribute to society.

A better understanding of who these people are and the natural value they have as fellow human beings lies at the heart of the problem. In addition, there’s a great need to change and adapt laws that allow for affordable, scalable housing options like tiny homes that include a small kitchenette and shower. Goldberg discusses his ongoing efforts to develop unused farmland as a cooperative farm where residents would live and work using regenerative agriculture methods to support themselves and the surrounding community. Educating the public to the realities and true demographics of the unsheltered is a start. Laws that favor affordable housing can reduce the barriers to a greater variety of housing options. Finally, dignified, affordable housing solutions are already potentially available, but until attitudes and laws change, they go unused.

Mentioned in this episode

E Pluribus University

Thrive LA

Community First!

LAHSA

The People Concern

Homestead Act

Earthship Community

Trash Prophets

Housing Collaborative

The Global Bridge Foundation

Note: Below, you’ll find timecodes for specific sections of the podcast. To get the most value out of the podcast, I encourage you to listen to the complete episode. However, there are times when you want to skip ahead or repeat a particular section. By clicking on the timecode, you’ll be able to jump to that specific section of the podcast

Transcript

Announcer: (00:07)

The Missing Conversation, Episode 11.

Perry Goldberg: (00:11)

And so, on one side of the hill, you’ve got 60,000 homeless people, and on the other side of the hill, you have hundreds of thousands of acres of agricultural land sitting dormant.

Announcer: (00:23)

On this podcast. We will propose critical new strategies to address world issues, including homelessness, immigration, among several others, and making a connection to how our individual psychology contributes and can help transform the dangers that we face. We will break from traditional thinking, as we look at our challenges from a freer and more independent point of view. Your host Robert Strock has had 45 years of experience as a psychotherapist, author, and humanitarian, and has developed a unique approach to communication, contemplation, and inquiry born from working on his own challenges.

Robert Strock: (01:02)

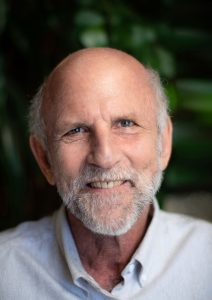

Welcome again, to The Missing Conversation where we address the most pressing issues in the world that the world is facing today and where we look for the most practical and inspiring programs and innovative ideas. Today, we have a very special guest who fits that bill perfectly, and that he is both extraordinarily grounded and devoted to use his resources, to inspire solutions to the many problems we face today. We’re going to narrow the focus to homelessness and agriculture and how the marriage between them could bring a solution that could scale throughout LA and the country. Carrie Goldberg is our guest and is the president of E Pluribus University, which he founded in 2013. Pluribus is a 501 c3 whose purpose is to develop innovative models for collaborative problem solving for global issues. At the age of 12, he devised a unique method for solving the Rubik’s Cube and beat the world record in 17 seconds, five seconds faster than anyone, which kind of blows my mind.

Robert Strock: (02:30)

He also started thrivela.org, which is an attempt to help solve the problem of veteran homelessness by creating a blueprint that could scale for modern homesteads in the Los Angeles high desert. He’s a graduate of Harvard University in the School of Law. In his practice. He’s helped clients obtain more than $1 billion of judgments and licenses. And he’s also purchased more than a hundred acres in different parcels with a clear intent of offering it free of charge to help solve the homelessness crisis. He’s been the most parallel thinker that I’ve met and creator of all alternative thought leadership in the area of homelessness that I’ve come across. And I’m very, very grateful to have met him. He’s a delight and an honor to call a colleague and I have been thoroughly inspired to share this path with him. Thanks so much for joining us Perry.

Perry Goldberg: (03:42)

Thank you so much. Your words are so kind, and it has been such a thrill to have gotten to know you and to find someone who shares this unique vision. It’s pretty amazing. And I’m so excited to be collaborating. Yeah, it’s been, it’s been really a mindblower to have such parallel thinking, not only with homelessness, but with immigration reform, but we’re going to narrow it today to just homelessness. So Perry, I know you’ve had an enormous amount of experience, you know, in the, uh, Palmdale area and that whole, uh, Antelope Valley. Could you give us a sense of what your vision is, and has been, with attempting to create a program for homelessness that combines it with regenerative agriculture? And I know you’ve largely focused on veterans as well. You know, I am a firm believer that every problem has a solution. The housing crisis is such an enormous problem, and it’s something that has been escaping solutions for many years.

Perry Goldberg: (04:52)

Very well-intentioned people have been trying to address various aspects of the housing crisis and are doing incredible work. And lots of people have been housed. And, you know, so many people have benefited from all of the tremendous, uh, efforts. And yet year after year, we see more and more homeless people, right? As we have some people, more people become homeless. So it’s, one thing is absolutely certain is that we need to do something different. We need to try something new. And as I started to study this problem, I thought about, you know, what, how are we solving? What are we doing now? And what, what might we do differently? And what I realized was, you know, the housing that we’ve been creating is so incredibly, incredibly expensive, trying to build housing in the city where land is expensive, the cost of, of new units there, is so expensive.

Perry Goldberg: (05:50)

I saw a statistic that it was 400,000 per unit, and that just doesn’t fit the problem. We have solutions that are, that are scalable to scale up to the size of the problem. And so it seemed pretty obvious that we have to figure out how to build much more affordably. And when you think about that, there’s the cost of the housing and there’s the cost of the land. So if you want to build affordably without subsidies, you have to build, um, smaller and you have to build where the land is inexpensive. And when I started researching, where is their inexpensive land? I realized there’s land right here in LA county. I was absolutely shocked. And there’s 400,000 acres of privately owned agricultural land in LA county that’s sitting dormant. And so on one side of the hill, you’ve got 60,000 homeless people. And on the other side of the hill, you have hundreds of thousands of acres of agricultural land sitting dormant.

Perry Goldberg: (06:52)

So that seemed like a real opportunity. And tiny houses, people love tiny houses, not everyone, but so many people love them. And if you are building tiny, you know, if you’re building something, um, 200 square feet, instead of an average 2000 square feet, it’s 1/10th of the size, it’s 1/10th of the cost because it’s a 10th of the labor and the materials. So, um, tiny houses and this agricultural land seemed to be handholds to me of these are very important pieces of the puzzle. So then going down that path of realizing how do you put these pieces together? It became clear that you can use this agricultural land to house people in what’s called farm worker housing, and we can get into that. But essentially, normally the land can only be developed with traditional housing, but when you have used farm worker housing, then you’re able to build tiny houses and house more people on the, on the land and create jobs, which is absolutely critical.

Perry Goldberg: (08:04)

If you’re going to house people in a rural remote area that they don’t have to queue very far for jobs. So putting together housing and jobs and community all together is really at the heart of the Thrive LA solution.

Robert Strock: (08:17)

So I, I think a couple points that I’d like to bounce off of, number one is the idea that we’ve been sharing is literally having a farm, be farmed by the homeless community. And I like to make reference to the one program that I know of that is doing something parallel, which is Community First, in Austin, Texas, where they have a farm. And that’s one of the options they have where they pay the workers. The homeless community is no longer homeless and they have an occupation. And then they insist they, that the workers are paid and that they also pay rent, which really inspires a self-esteem and also legitimizes the fact that their workers, which relates to what you just mentioned about the way the law is structured.

Robert Strock: (09:18)

That farm workers are allowed to have housing. Whereas if they were just simply a homeless program, they wouldn’t be able to have, have that.

Perry Goldberg: (09:29)

Yeah. So, you know, I think it’s important that we challenge a lot of our assumptions here. And then one of the assumptions that a lot of people have about the homeless and the housing crisis is that people who are homeless are homeless because they have a substance abuse issue or mental health issue, or a devastating physical disability that prevents them from working. And they can’t be productive members of society, but we’ve obtained statistics from LAHSA, um, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. And it turns out that the majority of the homeless actually don’t have any of those problems. And, uh, there’s an annual conference of Mayors. And at the Mayor’s Conference, they determined what are the main causes of homelessness?

Perry Goldberg: (10:15)

The top three causes that are all economic causes it’s that the rents are too high. People don’t have enough income and people don’t have enough savings. And so, um, we don’t have to assume that the only solutions are to create, you know, wraparound services and, you know, supportive housing for people. There are other ways that you can create housing options and ideally these alternatives are going to be self-sufficient and sustainable and scalable to, because we can’t just keep throwing money at the problem. And so, yeah, having a system where people are paying for their housing and people have real jobs with real money, you know, that’s really important and it’s very doable. So I would say people assume you have to have new housing where the jobs are, but what if you make the housing where it’s affordable and then you work on how do you create jobs where the housing is?

Perry Goldberg: (11:11)

So I think we can flip the problem, cause the housing aspect has proven to be, you know, somewhat intractable as a problem. But I think creating jobs where there’s agricultural land, that’s actually not very difficult to do at all.

Robert Strock: (11:26)

And I think today we’re looking at what we both perceive to be the majority of the homeless community and as has been made clear in other episodes, uh, we’ve written five white papers that are talking about separate other communities that would deal with issues of addiction, addictions of mental health. But in this community, we really would be dealing with the higher functioning, uh, majority of homeless people, which really I know blows the stereotypes. But I think that’s part of what we want to reinforce today as we’re talking.

Perry Goldberg: (12:03)

Absolutely. And you know, I get emails constantly, you know, many a week, many each week from people who have housing, but they’re really, you know, they find the thrivela.org website.

Perry Goldberg: (12:15)

And they really liked that idea of having, you know, just a higher quality of life to be more connected to nature and to have, you know, less stress. So many people are working three jobs to be able to make ends meet and the idea of having a simpler life living smaller that’s, you know, uh, that’s really appealing to people. And so if we were to create this housing option in the Antelope Valley where people could be living on a collaborative farm, for example, and having a much lower cost of living, you know, you’d have people leaving the city. Some people would leave the city for that opportunity, which would then have the effect of lowering the demand, you know, for housing in the city, lowering rents and making more housing units available in the city. So you could indirectly address the housing crisis in, in that way as well, even just by creating housing for people who already are housed and who really, there is a, I can tell you from firsthand experience, there’s a big pent up demand for this type of housing option.

Robert Strock: (13:21)

Yeah. And we both know that it’s going to get even bigger. Uh, once COVID is, is really dominantly resolved, that there’s a whole bunch of people that have been just barely surviving because of federal legislation, that that community is going to become even larger. So how long have you been attempting to get approval and what have you found to be your greatest challenges?

Perry Goldberg: (13:47)

Well, I started the project back in 2015 and bought my first piece of land in Acton back in 2015. And when I went to LA County to talk to them about what I could do with the property, uh, they basically said candidly, they said that it was a group of them talking to me and that, uh, you know, this is the county and you know, you can’t do anything in the county without a permit. And I said, well, um, you know, really, I said, can I walk on the property?

Perry Goldberg: (14:19)

And they said, yeah, you could walk on it. And I said, can I run on it? Can I sit on it? Yeah. Okay. Can I sleep in a tent on it? And they said, well, yeah, actually you can sleep in a tent on it. I said, can I invite a friend? And they said, yeah, you can invite a friend. I said, okay, well, there are some things I can do on the property without a permit. Um, you know, but over time, um, as I have tried to actually do things on the properties, it’s proven to be extremely difficult. The county is very, very proactive with finding if, um, if you are starting to do things on the property, like they really are watching you like a Hawk. Okay. Um, it’s amazing. Uh, and I guess, uh, particularly inactive, which I love and I now live in Acton, and I, I love my neighbors, but people are very concerned about, you know, what’s going on in the neighborhood and they call the county right away.

Perry Goldberg: (15:14)

If they see any activity on vacant land, they don’t want, um, I, pretty much every community doesn’t want affordable housing and they don’t want, um, they don’t want crime in their neighborhoods. People are worried if you have low-income people coming in, there’s going to be problems. Right. Um, and so, you know, the county is very focused on, on that aspect. Um, and, but they’re not focused on how do you make development happen? How do you say, how do you say yes, they really know very, very well how to say no, there are a thousand pages of rules and regulations, and they’ll hit you with one of those rules and regulations. And then in return, I tried to get permission from the county to use one of my properties as a farm. And the county will not agree to give you an address unless you have a building permit.

Perry Goldberg: (16:08)

So it makes it very difficult to do anything if you don’t have an address. And it’s nearly impossible to get a building permit in LA County because you have to have a source of water and you have to jump through many other hoops that are difficult in rural areas. Um, and so you can’t get an address. They will not agree to give you a permit for electricity for a farm, unless you have a single-family residence on the property. So for agriculture, it’s difficult to do a lot of things if you don’t have any power. Um, and there’s so many different, uh, hurdles. And essentially, even though in my very first conversation, they said, you can sleep in a tent on your property, more recently they’ve said, you need a building permit. If you want to put a tent, any kind of tent, like the kind of tent you’d go in the woods and pitch yourself, the kind that you can carry and takedown, you know, in one minute, they, they’ve told me, and I have this in writing that you need a building permit in order to do that.

Perry Goldberg: (17:07)

So, uh, you know, the, the powers that be for whatever reason, don’t, uh, they’re not keen on having things happening up there at the moment. And I think that it’s really, that really needs to change. So it’s been a while that I’ve been at it.

Robert Strock: (17:26)

Yeah. And I think we both, I know we both agree that having the community be as far away as is needed to not be threatening to another part of the community or worried about either crime or worried about property values is the most sensible solution. And having it not be so far out that medical issues or needs to be connected to the city with transportation, finding that middle ground is the most common sense approach and narrowing in, uh, with, with People Concern and John Maceri, which we’ll get into a little bit later with approaching the City of Palmdale and attempting to make a very concrete proposal with them on a number of options of land, including yours.

Robert Strock: (18:23)

And we have the 125-acre parcel. I think we’re, we’re really, uh, uh, let’s say doing our best to reduce the obstacles, to reduce the concerns that people have and be as practical as we can. And we know we have the ability to get either solar power, which I know we both prefer, uh, as well as water that would almost for sure be the water that would be pumped. Uh, and that, that is very viable. So what do you think is needed to be understood by both the public and the political powers that would really give a chance to take care of this problem that all of us are facing and all of us are in together?

Perry Goldberg: (19:11)

You know there are a few different pieces I’d say that needs to be understood. I think one is to differentiate that rural land is a really important piece of the puzzle and that we need to be thinking about what kinds of solutions, what would solutions look like if we’re going to be using rural land because it’s just not been part of the conversation at all.

Perry Goldberg: (19:34)

So that’s an important one. And I’d say related to that is just thinking about history. When Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, in July 1860, someone could move and, and choose 160-acre parcel anywhere in the country that was owned by the federal government. And if they built their own home and lived on the land for five years, it was theirs. And 600,000 Americans, the pioneers did that. And every single one of them was homeless. When they showed up, there was no home there and they built their own home and that kind of pioneer spirit, you know, we sort of, uh, romanticize and, and for good reason, we hold those people up in high esteem. Um, but we don’t even imagine that anyone could possibly do that today, even though people did it so long ago when there were no roads and no power tools, no Amazon, et cetera.

Perry Goldberg: (20:26)

Right. You know, it’s just so much, so much easier to do things yourself today than it was then, but we don’t let people, the rules and regulations don’t allow self-sufficiency. So I think, you know, when it comes to the desert, people say, oh, it’s too hot, it’s too far. But I think people need to recognize it is doable that we can live out in the high desert. There are many examples all around the world, including in New Mexico, the Earthship Community, that’s completely, self-sufficient, off-grid housing. So the, the question is can you do it a hundred percent and you can do it and why aren’t we doing it? There’s only one reason we’re not doing it and it’s rules and regulations. And so when we think about what are, you know, you want to solve a problem, you need to understand the causes. And from my, you know, all of the work I’ve done, I would tell you that one of the most significant causes are the rules and the regulations that block solutions like this.

Robert Strock: (21:31)

Yeah. I know from our conversations, it’s rules, regulations, and not in my backyard, um, correctly, the combination of all of the above. So I think that for the public to hear and the political, uh, people that are empowered to hear that there’s this incredibly viable solution that isn’t even very complicated, that simulates what you just described as the homestead that doesn’t require 160 acres for one person. It requires maybe five acres or 10 acres for 10 people or 20 people. And these are people that can be well supervised and can be picked if they’re anywhere near a neighborhood to be utterly safe. And the precautions that are needed will be taken. And, and I think that it’s going to require both a public openness to have somebody be a mile away, uh, and the rules and regulations to be adopted to see this marriage between the agricultural community and the homeless community.

Robert Strock: (22:42)

One other question, you and I have talked about that. I thought you had a better answer than I did, uh, which was, why do you think there’s such a resistance to tiny homes that are dignified that actually have a tiny little shower and a tiny little kitchenette versus what started to be adopted in California, which is a pallet shelter, which is 64 square feet. And it has an outside bathroom, but it doesn’t have the feel that’s going to lead to, ah, I’m home in my community. Uh, I’ve, I’m so grateful to be here and it’s much more of a feel of temporary shelter and not one that you’d want to live in and have a pride of community. Why do you think there’s that resistance to tiny homes, which by the way, for the public to now, right now, there’s 75 different manufacturers that we know of that are manufacturing, tiny homes.

Robert Strock: (23:40)

So there’s an abundance of scale capacity.

Perry Goldberg: (23:44)

I think a number of different factors, number of different things that are going on. And, you know, there’s traditional resistance we’ve had in the United States, issues with exclusionary zoning for more than a hundred years. So communities erect, all sorts of, uh, regulations that try to, um, preserve property values, uh, keep neighborhoods a certain way that the residents like, um, a lot of people are very resistant to change and there’s a fear of the unknown. And so, um, when it comes to tiny houses, I think people worry, you know, who’s going to be living in these tiny houses, if they’re so tiny and they’re so affordable, um, you know, is it going to be an undesirable element? That’s, so that’s one issue. Is it going to hurt their property values? Is there going to be crime? Is it going to be unsightly?

Perry Goldberg: (24:38)

You know, I think when you see, um, some low income areas, there might be a tendency that they’re not well-maintained, maybe the people who live there can’t afford to maintain them, or they’re dealing with issues that make them less likely to maintain their homes and keep them looking nice. So there’s a general resistance, I’d say everywhere to having low-income housing coming in. And then when it comes to the Antelope Valley, there’s a whole other layer which has to do with the water, because they’re, the groundwater there, the levels of the groundwater go down. And there’s a lot of, a lot of people are on wells. And a lot of the farms there are, there already are some farms there and that are using groundwater. The first class action in US history relating to groundwater rights was in the Antelope Valley. And it was resolved a few years ago.

Perry Goldberg: (25:32)

And the people who already have wells settled amongst themselves and agreed no one else is allowed to drill a well. Uh, so basically having more people coming into the Antelope Valley means that water is going to now have to be, you know, split among more people. And if you have to drill your well deeper, that’s real money out of your pocket. So the water is another issue. Um, and you know, I think there’s just general nimbyism right. You know, not in my backyard, like you said, uh, part of the Thrive LA approach is to address that head on. And so our thinking is you really need to take that seriously because there are very good reasons why people are concerned. They’re legitimate reasons, and you want to put people’s minds at ease. And so our thinking is we’re going to be screening all of our community members very carefully to ensure that they have what it takes.

Perry Goldberg: (26:26)

So we’re going to be training people on the agricultural techniques so that they can be productive members of a collaborative farm. And we also have developed a curriculum for effective communication and interpersonal relations to help maximize the odds of success in terms of people being able to get along with each other. And only people who are successful with the training will be invited to become permanent members of the community. So that hopefully puts people’s minds at ease in terms of who’s going to be there. And then we also are, intend to require that the community members not just do a great job of taking care of themselves, but that they also clean up the surrounding area because in the Antelope Valley for anyone who’s been out there, you see, there is a tremendous amount of trash that has just been dumped. It’s a major, major problem.

Perry Goldberg: (27:16)

So, uh, you know, out in, uh, in the desert, there’s trash everywhere. And our idea is that we’ll clean up the one-mile radius around each thrive LA community. So people will be thrilled that this community is there. It’s actually going to make the neighborhood much better.

Robert Strock: (27:33)

Yeah. One of the other people that we’re going to be interviewing has a program called Trash Prophets, PROPHETS. And what they do specifically is go into the neighborhood, clean it up, gather bottles and cans, and it’s another source of income. So mixing that in is really viable. In addition, the tiny homes are beautiful. They, they, they look really like quaint, uh, houses that are made of wood, wood exterior, or at least a veneer of wood. And they are absolutely beautiful. And I think that the key thing is, especially if people are listening right now from the Antelope Valley to really recognize that fear, you know, from my psychological backgrounds, let’s say, when you’re talking about a lot of the concerns of fear, there’s going to bring property values down, fear that there’s not going to be safety.

Robert Strock: (28:32)

Those fears need to be met with sensible conversation with reassurance in the ways exactly that you’re talking about. And I think that’s what we as a team can do because we’re resourcing not only with ourselves but with prominent programs in Los Angeles that are already doing the best work in homelessness. And as I mentioned, we’re, we’re approaching, uh, Palmdale in this next week, uh, with People Concern, which is the largest provider of permanent supportive housing in Los Angeles County. What do you think the listener can potentially do to protect, to really help, uh, spread the word, get involved? What are your thoughts of what somebody can do if they’re just, just an ordinary person that’s maybe living in your neighborhood or any neighborhood? Cause we’re talking about this, applying in a number of areas, in addition to the Antelope Valley.

Perry Goldberg: (29:33)

You know, the homeless conversation is just being had constantly the LA Times. You know, it seemed like every day it was on the front page of the LA Times. Uh, and I think that you know, when people are engaging in a conversation about the housing crisis, they can ask other people, Hey, you know, what do you think about a rural solution and not having agriculture as part of it? What if, what about tiny houses? Should we be thinking about that? Um, you know, so if people start thinking about it like that, um, that’s, that’s one simple thing that can be done. Um, you know, when it comes to the tiny houses, um, they can be a beautiful, actually, if you’re building something that’s only 1/10th of the size of a traditional home, then when you’re furnishing it, you know, when you’re thinking about what’s the flooring that we’re going to put in there, right? You can go for the higher-end items because you’re only doing it for a very small number of square feet.

Perry Goldberg: (30:38)

So you can make it super upscale, like a, you know, a Ritz Carlton hotel room, which is a very small space, but it’s really fancy. It, there’s no reason that it has to be spartan. And I have seen some that are very, very spartan, which I think is just unfortunate because it gives the tiny houses, it makes the public wary of, of these tiny houses. You want people to say, I would love to stay there. I’d love to be in this place. Right. I think that’s an important piece of it. Um, you know, so people can just be sharing with others that how, hey, on HGTV, they’ve got this great show on tiny houses and they’re so beautiful and that’s a wonderful place to live and wow, wouldn’t it be great to be more connected, to nature and have a job where you can be outside and be with other people and not have to commute and have a really low cost of living. So you’re not stressed out about how you’re going to pay your rent. You know, doesn’t that sound nice.

Robert Strock: (31:36)

Yeah. I think those are great, great practical conversations, a couple of other things. I think there’s a nonprofit corporation that, that is called the Housing Collaborative. They’re the ones that are really showing the 75 different kinds of tiny homes for the listener to actually go there and see the beauty of what’s there for people to have a conversation with themselves about the fact that, you know, what we’re not dealing with our fear. We don’t really like walking down the street and having to walk by someone that’s unsheltered. Cause we feel scared or we don’t like it when we’re waiting by a stoplight and somebody comes up to our window, but we’re not willing to even allow the possibility of having a community formed a mile away and, and seeing the lack of rationality, individually and collectively that is there because of fear and finding our courage, you know, finding our courage to say let’s be in it together.

Robert Strock: (32:38)

And I think, I think that’s a really key element and then one other free-associative thing that’s a little bit different than what we’re talking about is that the accessory dwelling units now have been passed throughout the state, that they could become legal and another element of what’s possible and supplemental to what we’re talking about is, is to possibly consider and have people talk about the idea that maybe the city, the state, the county, federal government could provide a stipend of $700 or $1,000 to the people that have an accessory dwelling unit and possibly include those, uh, in there. And that thousand dollars could be the difference between somebody struggling or not. And they can be carefully pre-screened psychologically and without, without a prior history of arrest and have that sense of security be added as well, so that there really are a lot of solutions here. If we can just face this together.

Perry Goldberg: (33:38)

Absolutely. You know, and the ads are really interesting because with the ADU processes, accessory dwelling units, or, you know, guest homes or granny flats that refer to, uh, they’re allowed to be smaller than the normal in the unincorporated areas of LA Counties minimum square footage is 800 square feet for a single-family residence. But for an ADU, it could be much smaller than that. And so, you know, those are allowed that’s, you know, perfectly reasonable housing. Um, and it really begs the question of why can’t we do that as just the primary house? Why does it have to be only a secondary house? Why do you have to have a single-family residence first, if we were to allow people to do an ADU size home and also on an ADU side, an ADU schedule for the permitting because by law it’s supposed to be a four-month ministerial process for getting a permit for an ADU versus over three years is the norm and LA County, uh, in an unincorporated area.

Perry Goldberg: (34:40)

So we also should have pre-approved, um, plans that anyone could just off the shelf, maybe you’re paying an architect $500 to use his or her plan, but it should be very, very simple. We need to be very proactive at the governmental level of making it as easy as possible for someone to buy a piece of land and develop it. And the ADUs are just a perfect example of how you can do that.

Robert Strock: (35:07)

Exactly. And, and just to go back to cover one of the things that you mentioned that you and I have discussed quite a bit, and I know we’ve, we’ve been on both ends of what type of agriculture might be, might be most optimal to use, but in a water area that is marginal, as we’ve shared in a number of our other episodes, regenerative agriculture uses 10 to 15% of the water that traditional agriculture uses, and that makes it a completely viable.

Robert Strock: (35:45)

And the ability to transform dirt into soil is a major part of that. So the viability of regenerative agriculture may be mixed with some permaculture, mixed with solar, mixed with housing that is really quaint, mixed with addressing the safety concerns. I think we really have narrowed in on something that collectively is viable to scale throughout the country. And I know you’re, you’re one of the, uh, actually not one of the few, you’re the only person that I’ve been able to talk about all of these things with, and have you be on the same page before I met you. So it is truly an honor to be able to share this with you. It’s a joy. Uh, I know I’ve made a lifelong friend with you, and I’m just very grateful that you’re sharing your experience, your wisdom in how we can really address this crucial problem that we’re all facing.

Perry Goldberg: (36:48)

I feel exactly the same way. You know, it’s, uh, it’s such such big problems that we’re talking about, and they’re so much bigger than any one person. Um, it’s very daunting when you feel like, you know, the problems are just much bigger than you are. Uh, and so you absolutely need to find like-minded people, allies, and people who have complementary skills and resources. So, uh, it’s, you know, it was so exciting to have met you and the team of people that you’re pulling together, uh, and to join forces. So, uh, it’s really needed, right? And I think the more people who hear about this type of approach and can get involved, the more likely it is that, you know, we’ll hire now, you know, the wrinkles, and then we’ll persuade people that this is something that should be taken seriously and needs to be considered.

Robert Strock: (37:44)

Yeah. One of, one of the things that, uh, people won’t be able to see is, are smiles at various times as it has, as we look at, oh my God, this is so simple. It seems so doable and just a plea and a prayer out there to the public to see this possibility. And I know we joined each other and I just thank you so much for joining me on the show today.

Perry Goldberg: (38:11)

Thank you so much, Robert, what a pleasure really appreciate it.

Join The Conversation

Join The Conversation

If The Missing Conversation sounds like a podcast that would be inspiring to you and touches key elements of your heart, please click subscribe and begin listening to our show. If you love the podcast, the best way to help spread the word is to rate and review the show. This helps other listeners, like you, find this podcast. We’re deeply grateful you’re here and that we have found each other. Our wish is that this is just the beginning.

We invite you to learn more about The Global Bridge Foundation—an organization collaborating to heal communities and the world at TheGlobalBridge.org.

Visit our podcast archive page